Orphism

Orphism is a religious and spiritual movement whose roots are lost into prehistory. It was born of the fundamental human need to respond to such questions as “who am I” and “where am I-my soul, that is -going after death”. It is likely that Orphism originated on the shores of the Black Sea and followed the roots of the trade of amber, which reached Greece latest by 1700 BC. Indeed, Baltic amber has been found in the Mycenean shaft graves of the 17th Century BC. The religious ideas that moved south along with the amber trade stemmed from shamanism. Foremost among them are ecstasy, metamorphosis and even migration of the human soul.

Orpheus, Dionysus and Ecstasy

Orpheus, from whom Orphism and its practices derive their name, belongs to legend. A master musician who enchanted even rivers and mountains, he descended into the underworld to bring back his beloved wife Eurydice, who died from snakebite and went to Hades. He charmed Cerberus, the hellhound, with his music and obtained her release. Metaphorically, Orpheus’ descent to Hades stands for his own death. The opening of the gates of the underworld implies his resurrection.

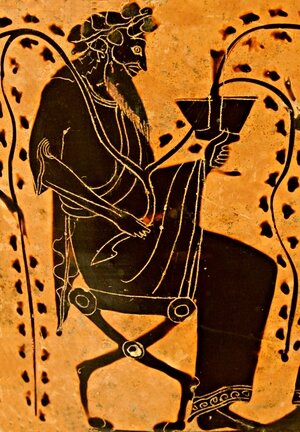

The main God of Orphism is Dionysus, who first died at the hands of the Titans and then was reborn. Through their ecstatic rituals, his worshipers reenact and re-experience his death and resurrection. Dionysus is the god of nature, of ecstasy and of freedom. He is also a god of opposites: human and animal, peaceful and violent, alive and dead, masculine and feminine, sacred and profane. Dionysus is much like the shamanic shape shifter, changing form and moving between polarities, disregarding limits and possessing his followers without the necessity of a priest or intermediary, just the worshiper in ecstatic dance.

The ivy is his emblematic plant and the power of wine is a natural force. Ivy leaves and vine tendrils envelop the practitioners of Dionysiac worship and unite them with the powers of nature. The next step into freedom, which is uniquely a gift of the god, is ecstasy, a state of soul and mind, which in a ritual context, frees the person from the bonds of artificial social structure. Ecstasy allows man to transcend his boundaries and become, even temporarily, possessed of God. This means that he can be a host to the god deep inside him. Ecstasy gives man the gift of metamorphosis; it frees him from the shackles of everyday life as well as of psychological wounds. It is for this reason that Dionysus is called “Eleutherios,” the god that frees.

Orphic Beliefs and Practices

For the Orphics, the body was a tomb and the spiritual entity we call the soul its prisoner. Orphism does not necessarily condemn the body, but it indicates that the body imposes material constraints on the soul and also teaches freedom from these constraints and, ultimately, resurrection. Vigilant purification of the human body was an Orphic practice. Orphics did not perform animal sacrifices; they respected animal life and abstained from eating meat. Violators of these taboos and of fundamental ethical laws had to undergo purification. Any transgressions would unavoidably drive a person into a cycle of punishment, both here on earth and even more so in the afterlife.

Orphics did not place great importance on cosmogony. For them, the world was born of an egg which hatched out Eros, who was later named Protogonos (meaning first born, primal). It was he who created the human race. For Orphism, this system of procreation was almost a conceptual metaphor, which stood for a quest for answers to metaphysical ideas about being.

Orphic Texts

In terms of Orphic texts per se, we have the Orphic Hymns which are most likely a product of an Orphic revival in Asia Minor (ca 300 AD). Essentially, they are prayers to various divinities whose attributes appear as lists of epithets. The purpose of these epithets is to provoke the powers of the divinities and to rally them in behalf of the initiates. The Hymns usually finish with a prayerful request for good health, a good end to life here on earth and prosperity.

By contrast, we have brief Orphic texts, mostly inscribed on tablets of gold, originating from various parts of the Hellenic world and dating from the 4th century BC to the 2nd century AD. These texts express in powerful ways a fundamental concern for the identity of the human soul and its ultimate destiny in the afterlife. The themes of eternal memory, eternal life, purification and rebirth through metamorphosis are central to the early world of Orphic religion and practice.

Orphism's Influence

Orphism’s spiritual messages, especially about the afterlife, were adopted into many mystery cults. Eleusis was one of them. Elements of Orphism certainly can be traced in the pre-Socratic philosophers whose ideas influenced Orphism itself. Akin to the Orphic practitioners, the Pythagoreans abstained from eating meat and believed in reincarnation. Empedocles also offers precious knowledge about Orphic ideas, as in the following fragment:

“Once I was a young man

I was a young woman, too

then I became a bush and then a bird

and now I am a quivering fish

leaping out of the sea.”

Later on, Orphic beliefs influenced philosophy, especially Plato and the Neoplatonic philosophers. Plotinus offers the best example of this interaction. In turn, philosophical movements, such as Stoicism, exerted tangible influence on Orphism. Traces of Orphic belief can be found in Homer, Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns. The Bacchae by Euripides is a fundamental text for understanding Dionysus and the dynamics of ecstasy.

Aspects of Orphism were embraced by several religions. It should be remembered that those who wrote the liturgical texts of the Christian church, especially the church fathers, had direct access even to more Orphic texts than we have today. They discovered in Orphism a great emphasis on spirituality and on the eternal life of the human soul.

Sufism is a spiritual path that contains many Orphic elements within it. A living example of this are the whirling dervishes of the Mevlevi order, who perform a ritual called Sema, in which they first appear in black cloaks, which they cast off to reveal white robes as they whirl in ecstasy. Their long hats symbolize the gravestone and the black cloak the tomb. When one watches this ceremony, one cannot help but think of the image of the soul being freed from its prison and the Orphic themes of ecstasy, metamorphosis and resurrection. The whirling dance conveys the impression of the soul spiraling upward into the sky. The soul and its journey have been depicted in many cultures as a spiral. It is also interesting to note that in different Orphic fragments, both Dionysus and Zeus are described as whirling.

“Hear me o Zeus, forever you whirl

in a circle of spiraling light”

539F

He was first to come to the light,

he was named Dionysus,

because he is whirling

throughout vast and lofty Olympus

540F

(Translated from Alberto Bernabe’s text of the Orphic Fragments)

The connection between the spiral movement and ecstasy is still very much alive in the circle dances of many parts of Greece. On the island of Ikaria thousands of revelers join to dance in the village festivals to the sounds of the lyre and a goatskin instrument called gaida or tsampouna. In their local dance, the Ikariotiko, the music hits a crescendo and the dancers leap into the air and shout in an expression of group ecstasy. In the dance the boundaries are transcended and the people become one movement, one cry. One can feel this today in Ikaria, as all dance together: the priest, the drunkard, the tourist, the young and old.

Video of Ikariotio dance at festival

Orphic Ritual

The details are interesting. However it would be a mistake to allow them to stifle our imagination and turn us into would be objective observers. How were the Orphic rituals during which the Orphic Hymns were sung? Almost two thousand years have passed since the probable century of their composition. Time has woven a lot of warp into the veil which covers both text and music. Only our imagination can help us conceive the distant image of what took place.

The initiates are gathered around their leader, the boukolos. Outside, darkness has sunk deep and persistent. In the hall of rites, candles are flickering and faces are not visible. A worshipful crowd begins to sway to the rhythm of a religious hymn. Shortly, clouds of incense spread everywhere and separate the initiates from their daily lives. Their chant becomes louder, rises to the gods. In the beginning, the music flows slowly. Then, it begins to ascend until, with a sound leap, it reaches a crescendo and then returns to more soothing notes. The incense, almost intoxicating, gives wings to hope for another life. The censor is swung in trochaic rhythms. All are silent and steeped in the sanctity of the moment.